This post was written by Ana Brandusescu, Carlos Iglesias, Danny Lämmerhirt, Stefaan Verhulst

The presence of open data often gets listed as an essential requirement toward “open governance”. For instance, an open data strategy is reviewed as a key component of many action plans submitted to the Open Government Partnership. Yet little time is spent on assessing how open data itself is governed, or how it embraces open governance. For example, not much is known on whether the principles and practices that guide the opening up of government – such as transparency, accountability, user-centrism, ‘demand-driven’ design thinking – also guide decision-making on how to release open data.

At the same time, data governance has become more complex and open data decision-makers face heightened concerns with regards to privacy and data protection. The recent implementation of the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) has generated an increased awareness worldwide of the need to prevent and mitigate the risks of personal data disclosures, and that has also affected the open data community. Before opening up data, concerns of data breaches, the abuse of personal information, and the potential of malicious inference from publicly available data may have to be taken into account. In turn, questions of how to sustain existing open data programs, user-centrism, and publishing with purpose gain prominence.

To better understand the practices and challenges of open data governance, we have outlined a research agenda in an earlier blog post. Since then, and perhaps as a result, governance has emerged as an important topic for the open data community. The audience attending the 5th International Open Data Conference (IODC) in Buenos Aires deemed governance of open data to be the most important discussion topic. For instance, discussions around the Open Data Charter principles during and prior to the IODC acknowledged the role of an integrated governance approach to data handling, sharing, and publication. Some conclude that the open data movement has brought about better governance, skills, technologies of public information management which becomes an enormous long-term value for government. But what does open data governance look like?

Understanding open data governance

To expand our earlier exploration and broaden the community that considers open data governance, we convened a workshop at the Open Data Research Symposium 2018. Bringing together open data professionals, civil servants, and researchers, we focused on:

- What is open data governance?

- When can we speak of “good” open data governance, and

- How can the research community help open data decision-makers toward “good” open data governance?

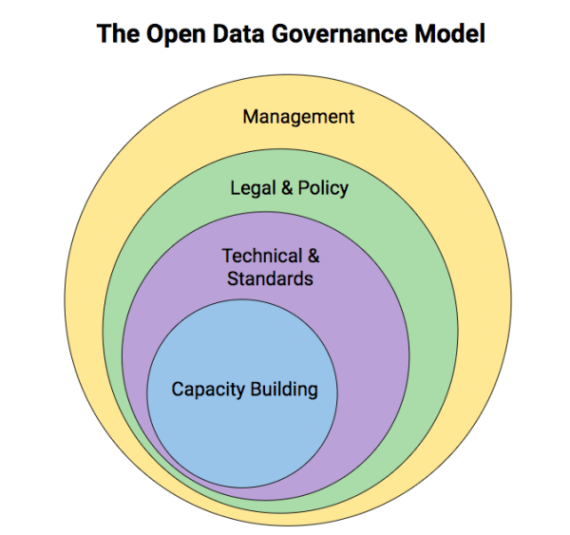

In this session, open data governance was defined as the interplay of rules, standards, tools, principles, processes and decisions that influence what government data is opened up, how and by whom. We then explored multiple layers that can influence open data governance.

In the following, we illustrate possible questions to start mapping the layers of open data governance. As they reflect the experiences of session participants, we see them as starting points for fresh ethnographic and descriptive research on the daily practices of open data governance in governments.

Figure: Schema of an open data governance model.

The Management layer

Governments may decide about the release of data on various levels. Studying the management side of data governance could look at decision-making methods and devices. For instance, one might analyze how governments gauge public interest in their datasets – through data request mechanisms, user research, or participatory workshops? What routine procedures do governments put in place to interact with other governments and the public?For instance, how do governments design routine processes to open data requests? How are disputes over open data release settled? How do governments enable the public to address non-publication? One might also study cost-benefit calculations and similar methodologies to evaluate data, and how they inform governments what data counts as crucial and is expected to bring returns and societal benefits.

Understanding open data governance would also require to study the ways in which open data creation, cleaning, and publication are managed itself. Governments may choose to organise open data publication and maintenance in house, or seek collaborative approaches, otherwise known from data communities like OpenStreetMaps.

Another key component is funding and sustainability.Funding might influence management on multiple layers – from funding capacity building, to investing in staff innovations and alternative business models for government agencies that generate revenue from high value datasets. What do these budget and sustainability models look like? How are open data initiatives currently funded, under what terms, for how long, by whom and for what? And how do governments reconcile the publication of high value datasets with the need to provide income for public government bodies? These questions gain importance as governments move towards assessing and publishing high value datasets.

Open governance and management: To what extent is management guided by open governance? For instance, how participatory, transparent, and accountable are decision-making processes and devices? How do governments currently make space for more open governance in their management processes? Do governments practice more collaborative data management with communities, for example to maintain, update, verify government data?

The Legal and Policy layer

The interplay between legal and policy frameworks: Open data policies operate among other legal and policy frameworks, which can complement, enable, or limit the scope of open data. New frameworks such as GDPR, but also existing right to information and freedom of expression frameworks prompt the question of how the legal environment influences the behaviour and daily decision-making around open data. To address such questions, one could study the discourse and interplay between open data policies as well as tangential policies like smart city or digitalisation policies.

Implementation of law and policies: Furthermore, how are open data frameworks designed to guide the implementation open data? How do they address governmental devolution? Open data governance needs to stretch across all government levels to unlock data from all government levels. What approaches are experimented with to coordinate the implementation of policies across jurisdictions and government branches? To what agencies do open data policies apply, and how do they enable or constrain choices around open data? What agencies define and move forward open data, and how does this influence adoption and sustainability of open data initiatives?

Open governance of law and policy: Besides studying the interaction of privacy protection, right to information, and open data policies, how could open data benefit from policies enabling open governance and civic participation? Do governments develop more integrated strategies for open governance and open data, and if so, what policies and legal mechanisms are in place? If so, how do these laws and policies enable other aspects of open data governance, including more participatory management, more substantive and legally supported citizen participation?

The Technical and Standards layer

Governments may have different technical standards in place for data processing and publication, from producing data, to quality assurance processes. Some research has looked into the ways data standards for open data alter the way governments process information. Others have argued that the development of data standards is reference how governments envisage citizens, primarily catering to tech-literate audiences.

(Data) standards do not only represent, but intervene in the way governments work. Therefore, they could substantially alter the ways government publishes information. Understood this way, how do standards enable resilience against change, particularly when facing shifting political leadership?

On the other hand, most government data systems are not designed for open data. Too often, governments are struggling to transform huge volumes of government data into open data using manual methods. Legacy IT systems that have not been built to support open data create additional challenges to developing technical infrastructure, but there is no single global solution to data infrastructure. How could then governments transform their technical infrastructure to allow them to publish open data efficiently?

Open governance and the technical / standards layer: If standards can be understood as bridge building devices, or tools for cooperation, how could open governance inform the creation of technical standards? Do governments experiment with open standards, and if so, what standards are developed, to what end, using what governance approach?

The Capacity layer

Staff innovations may play an important role in open data governance. What is the role of chief data officers in improving open data governance? Could the usual informal networks of open data curators within government and a few open data champions make open data success alone? What role do these innovations play in making decisions about open data and personal data protection? Could governments rely solely on senior government officials to execute open data strategies? Who else is involved in the decision-making around open data release? What are the incentives and disincentives for officials to increase data sharing? As one session participant mentioned: “I have never experienced that a civil servant got promoted for sharing data”. This begs the question if and how governments currently assess performance metrics that support opening up data. What other models could help reward data sharing and publication? In an environment of decreased public funding, are there opportunities for governments to integrate open data publication in existing engagement channels with the public?

Open governance and capacity: Open governance may require capacities in government, but could also contribute new capacities. This can apply to staff, but also resources such as time or infrastructure. How do governments provide and draw capacity from open governance approaches, and what could be learnt for other open data governance approaches?

Next steps

With this map of data governance aspects as a starting point, we would like to conduct empirical research to explore how open data governance is practised. A growing body of ethnographic research suggests that tech innovations such as algorithmic decision-making, open data, or smart city initiatives are ‘multiples’ — meaning that they can be practiced in many ways by different people, arising in various contexts.

With such an understanding, we would like to develop empirical case studies to elicit how open data governance is practised. Our proposed research approach includes the following steps:

- Universe mapping: Identifying public sector officials and civil servants involved in deciding how data gets managed, shared and published openly (this helps to get closer to the actual decision-makers, and to learn from them).

- Describing how and on what basis (legal, organisational & bureaucratic, technological, financial, etc.) people make decisions on what gets published and why.

- Observe and describe different approaches to do open data governance, looking at enabling and limiting factors of opening up data.

- Describe gaps and areas of improvement with regards to open data governance, as well as best practices.

This may surface how open data governance becomes salient for governments, under what circumstances and why. If you are a government official, or civil servant working with (open) data, and would like to share your experiences, we would like to hear from you!

For more updates, follow us on Twitter at @webfoundation and sign up to receive our newsletter.

To receive a weekly news brief on the most important stories in tech, subscribe to The Web This Week.